The market value of the carbon credits is expected to exceed $50 billion in 2030. Many businesses globally are endorsing carbon credit strategies to meet their net zero target. However, the scheme has equally gathered a handful of criticism for not being transparent.

When booking an airline ticket, we often have an option to offset our emissions by paying a little extra. By doing so, we are essentially buying voluntary carbon offsets.

Businesses have options to apply the same principles. In a way that counts as reducing their carbon footprint and contributing to environmental conservation efforts.

Carbon credits

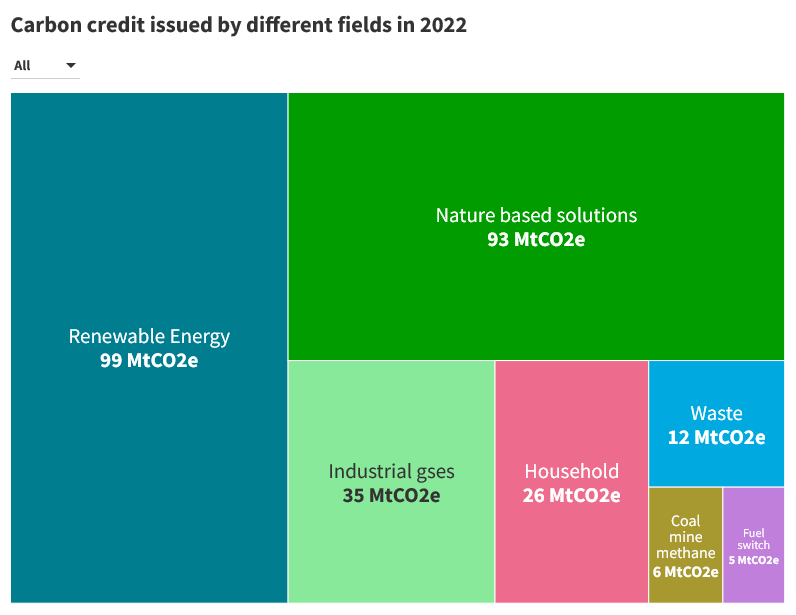

One carbon credit equals one CO2 tonne, obtainable by both businesses and individuals through the voluntary carbon market (VCMs). In 2022, renewable energy and nature-based solutions (NBS) projects became the dominant category for credit issuances (Figure 1).

Related: Solar energy facts: a win-win for businesses and the planet

As the carbon credits market gained huge exposure in the last decade, it is expected to grow from $414.8 billion in 2023 to $1602.7 billion by 2028. However, as healthy as this trend is, concerns have grown about it serving as a form of "greenwashing," where major polluters essentially clean their image by purchasing credits.

Given the complexities and opacity of the market, the most significant criticism comes from environmentalists who argue that credits like this fail to motivate businesses to alter their behavior but allow them to simply pay for their emissions.

Current challenges of carbon credits

The issuance and retirement of carbon credits experienced tremendous growth from 2016 to 2022 (Figure 2), mostly driven by the swift rise in corporate net-zero commitments.

However, participants experienced increased complexity surrounding the markets in 2022. As a result, the year saw a significant decline of 21% compared to 2021, resulting in a total of 279 million tons.

The drop in last year's issuance can be attributed to evolving policies regarding the eligibility of certain credits. Various governments and regulators exhibited a growing interest to provide much-needed clarity regarding VCMs. Some of them are:

The International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) initiated a public consultation on enhancing the resilience and integrity of VCMs.

The US Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) invited public input concerning climate-related financial risks within derivatives and commodities markets.

The UK Climate Change Committee (CCC) has called for government guidance and regulation of the markets.

What does this mean for the businesses?

Carbon credits essentially serve as a "permission slip" for emissions but the diverse range of criticisms could potentially hinder market growth.

Despite that, many companies have heavily deployed the scheme in their business strategies. Around the world, two-thirds of the world’s biggest companies are using carbon offsets to help meet their climate goals. Figure 3 shows from where some of the top companies are buying their carbon credits in between 2020-2022.

Chevron for example buys the majority of its credits from Colombia whereas Shell relies on Peru and Indonesia.

But many companies, such as Shell, Amazon, Deutsche Telekom, Samsung, and Google have also stated that they will use offsets in addition to their primary efforts to minimize and reduce emissions.

For critics, the thought processes are different. Greenpeace recently published an investigative article by Climate Home News that revealed questionable accounting practices in several carbon offsetting projects in China involving Shell. The article emphasizes that purchasing low-cost carbon credits and actively promoting them undermines the core purpose of carbon neutrality initiatives.

Another major player in oil and gas, BP has shown its intention to meet its 2030 emissions target without relying on offsets but acknowledges that offsets may help it exceed those objectives.

Without a doubt, establishing a strong position in the carbon credits landscape is advantageous for companies among their peers. However, they must identify key communication strategies to mitigate reputational risks.

Top players in the carbon credit market

Following the implementation of its emissions trading system in 2021, China became the global leader in carbon markets, exceeding the EU's by a factor of three.

The NBS projects, such as conserving and managing forests, and oceans are the second most popular category after renewable energy. Figure 4 shows the top 10 countries hosting NBS for carbon credit issuance in 2022.

How much do carbon credits cost?

Pricing can vary depending on factors such as project type, size, location, and other relevant determinants. Figure 5 shows the average carbon credit pricing by type in 2023.

The Paris Agreement proposed to keep the price in the $40-80 dollar range to limit global warming to 2°C. But at the moment, the average global price is $6 per ton, which is too cheap to meet this goal. The worry is that for many companies, it is like taking a bucket of water out of the sea.

Do carbon credits actually help reduce emissions?

Carbon-offset initiatives rely on effective tracking of credit purchases and sales. However, it's common for registry entries to lack clear identification of the company or organization involved. This sole drawback raises a huge question on the credibility of this scheme.

But if transparency was not an issue, carbon trading could potentially play a crucial role in mitigating carbon emissions today, which will facilitate more substantial reductions in the future.

Although the full extent of its success in achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 remains uncertain, they are expected to remain a significant component of climate strategies. But companies should focus first on directly decarbonizing their value chain and keep the carbon credits as a last resort.

It's great that you are highlighting the role of carbon markets in helping the world meet net zero targets. Unfortunately your article confuses two very different types of carbon market and I think that leaves the reader with the wrong impression.

Carbon credits are generated when companies voluntarily invest in projects such as reforestation that avoid emissions or capture carbon from the atmosphere. Yes, some companies have used the credits generated to offset their emissions elsewhere, but in the main those companies that are invested in the carbon credits also make an outsized contribution to cutting their own emissions. https://carbonrisk.substack.com/p/carbon-credits-a-license-to-decarbonise. The carbon credit market is only ~$2bn currently but has the potential to be worth multiple times that amount over the next few decades https://carbonrisk.substack.com/p/a-one-trillion-dollar-business.

Carbon allowances on the other hand are very different. They are part of regulated compliance markets introduced by governments to cap emissions. Obligated companies must buy carbon allowances to cover their emissions, and each year the cap goes down. They are a much bigger market than carbon credits. Covering about 18% of global emissions compliance carbon markets traded ~$900bn last year with the EU accounting for $750bn https://carbonrisk.substack.com/p/carbon-markets-are-going-global